Standard vs custom made soft contact lens fit: place your bets!

New insights into specialty contact lens practice have led us to revisit the way we should be

fitting soft contact lenses in the current technology era. More than ever before, leading institutions and practitioners advocate for skills and expertise to be brought back into soft

contact lens fitting2.

The main driver being the fact that ongoing advancements in contact lens materials and advanced optics have not succeeded at reducing the number of dropouts. Arguably, we may wonder whether the commoditisation of the contact lens category has played a role in this subject by oversimplifying lens fitting and somewhat negatively impacting our standards of care in clinical practice. In the present review, we will highlight some of the patient-, lens- and practitioner-related factors that should be considered in order to improve lens fits and on-eye performance, as well as patient satisfaction rates in the long-term.

Soft lens fitting background

Research by Rumpakis and colleagues (2010) showed that reduced comfort, especially related to dryness; decreased or unstable vision; and compromised eye health were common findings in lapsed contact lens wearers3. Their 30% drop-out rate estimation is still assumed to be valid at present in Europe, which to certain extent could explain why the category has remained relatively flat for several years. A survey involving over 16 thousand subjects highlights that 33% of wearers drop out within a period of 3 months after the initial fit, while one in 10 simply give up at the initial 2-week trial period4. This lays emphasis on the role of the eye care practitioner in identifying and preventing early signs of a sub-optimal contact lens experience. Dropouts carry economic implications in terms of revenue, loyalty and practice building3. Therefore, we shall aim at getting better understanding of the different components involved in a perfect contact lens fit.

Managing a successful contact lens practice requires a careful, individual assessment and understanding of the “human factor”. From your initial consultation to the final lens fit: everything should revolve around the patient. Current practice standardisation, however, tends to disregard patients’ individuality. Epidemiological studies show a significant variability for biometric data in healthy eyes, primarily corneal size and shape. Similarly, ocular surface physiology also affects contact lens comfort in a unique way, particularly as it relates to tear film composition and stability, eyelid muscle tone, blink dynamics and eyelid wiper integrity. Finally, optical factors such as ocular aberrations, pupil size variations and the accommodative response can also vary considerably among the optometric population. With all these variables in mind, it should be appreciated that there is probably no one single factor that would guarantee a successful contact lens wear for every patient. Following a systematic approach may be the best strategy (Figure 1).

Getting the basics right

In designing your strategy, it is important to reemphasize that a thorough patient history should always be your starting point. Underlying systemic or ocular diseases or medication intake/topical application may compromise contact lens comfort. Patient’s occupation, lifestyle and the environment in which the lenses will be worn as well as their motivation and expectations are critical to assist you in contact lens recommendation. Ultimately, patients’ subjectivity will be integral to contact lens success and that’s why you should ensure goodquality discussions and interactions are taking place with your patients at all times.

When it comes to contact lens selection, you may start by looking for the best match between patient needs and the standard lenses that are readily available to you. Lens modality (daily vs frequent replacement) and contact lens material (silicone hydrogels vs modern hydrogels) will usually be the key filters when narrowing down your selection.

Regarding lens materials, it is now acknowledged that silicone hydrogels are not the holy grail of contact lens-related comfort5. Some patients will be best suited for silicone hydrogel contact lenses. But, for those who do not experience the benefits of a lens with silicone, polymer engineering has now overcome some of the flaws of conventional hydrogels by introducing the latest generation of biomimetic hydrogels5. Ori:gen technology applied to the award-winning Gentle lenses by mark’ennovy feature a homogenous cross-linking agent to produce a unique, extra-porous matrix whilst ensuring that the lenses undergo less than 1% dehydration. Their extremely low coefficient of friction (CoF 0.05), which mimics the lubricity of the cornea itself, also accounts for lens wettability and a natural wearing comfort. As a clinical tip, bear in mind that a suite of contact lens materials should be available in your clinical toolkit for you to choose based on patient’s physiology and needs.

The strategy is pretty straightforward until it comes to the physical fit of the lens, at which time eye care practitioners may start to face some challenges. The limited geometries and parameter range of mass-produced contact lenses and the “one size fits all” approach are some obvious ones. Technological advancements in contact lens mapping provide some insightful observations. One of the most important is that corneal sagittal height should be the most relevant variable for contact lens selection, as it a much better predictor of lens behaviour on eye than central k-readings6.

Although the “sag” language may be familiar to scleral and specialist lens fitters, we may wonder whether it could be equally meaningful to soft contact lens practitioners. We will first focus on corneal diameter for practical reasons: it has shown good correlation to lens performance on eye and it does not require any sophisticated piece of equipment; both of which provide a good reason to include it into our routine contact lens examination. Measuring horizontal visible iris diameter (HVID) can easily be performed with a specific ruler. Studies conducted at the Pacific University College of Optometry found that in 200 consecutive

eyes HVID values ranged from 10.9 to 12.6 mm, with an average value of 11.8 mm1. Approximately 27% of eyes fell outside the 11.3 to 12.2 mm diameter range that can be optimally fitted with an off-the-shelf contact lens.

Expanding our imaging capabilities from the gold-standard corneal topography into the limbus and beyond the corneal area has been instrumental to our current understanding of the anterior eye segment as a whole. Using optical coherence tomography (OCT) and ocular profilometry, average ocular sag was found to be 3735m±186m at a 15mm chord for healthy eyes7. While some ocular sag studies set its variability range at 900m in the normal population, research looking into sag values for available standard soft contact lenses suggests that these may be just covering about one third of that normal range8. Again, this suggests that some corneas will require a contact lens outside the so-called standard parameters.

When it comes to lens attributes, commercialised daily disposable and frequently replacement contact lenses claim fairly similar base curves and diameters. Independent studies by Montani and van der Worp reported marked differences in sagittal height among different brands as well as differences between labelled and true parameters6. In addition, little information is available on peripheral lens designs and edge configuration, which could assist in predicting how the lens will fit on the eye9. It looks like fitting a standard lens could be best described as an empirical exercise: you try the lens and somehow hope it will fit nicely on the cornea.

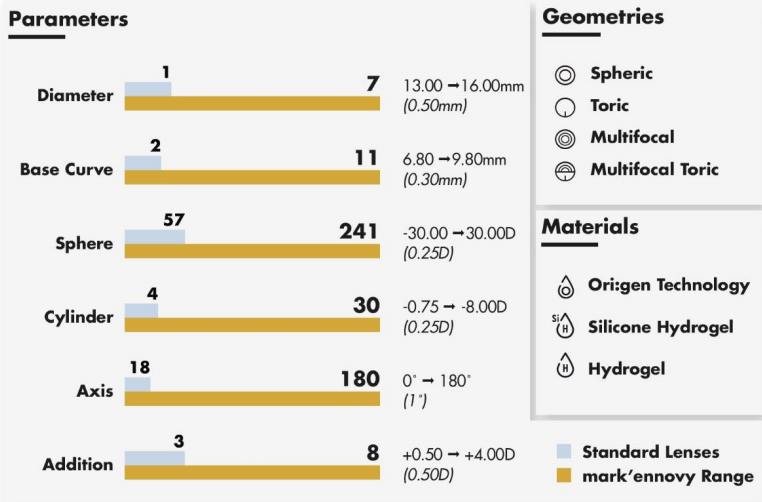

But what happens when the lens performance is not optimal? It is then when the flexibility of choice in lens parameters and geometries, together with the customisation options in lens design, become critical to achieving the best lens-to-cornea fit (Figure 2). Pupil size/dynamics and ocular aberrations could guide the most advanced optical designs, such as multifocal, multifocal toric or aspheric designs. For instance, mark’ennovy’s Smart Multifocal Technology optimizes its optical zone diameters for every addition and CD/CN designs in order to account for the differences in visual requirements as well as the natural evolution in pupil size. This allows for an optimal match between each individual eye’s needs and the power distribution across the lens profile, which results in an improvement in visual outcomes.

Conclusion: Place your bets!

The uniqueness of each eye as well as other patient-related factors will explain why a more personalised approach involving custom-made soft lenses is required to optimally fit a substantial portion of your own patient database. Fitting soft, custom-made lenses differentiates yourself as a high-profile eye care practitioner, and your practice as one that stands out for better patient satisfaction and retention.

Figure 1

A systematic approach to fitting custom-made, soft contact lenses by mark’ennovy qualified Customer Services team:

- Start with your patient consultation. Record updated spectacle prescription, visual acuity and eye dominance. Collect biometric and corneal curvature data.

- Measure HVID at 45 degrees and add 2.5 mm to determine lens diameter (). HVID should be your leading parameter.

- If necessary, seek our expert advice on material and geometry selection, including customisable lens design options.

- Use manufacturer’s lens factor table to determine first lens choice based on input data ( and Km), the material’s properties and the overall lens design.

- Assess on-eye performance: verify lens centration, lens movement and lens stabilisation. Evaluate visual acuity and physiology as well.

- Use fitting tips to compensate for any cyl rotation. Multifocal optimisation should follow.

Figure 2

mark’ennovy unrivalled combination of parameters, geometries and soft materials give you unlimited options to fit a perfect lens to your patient’s eye.

REFERENCES

- Caroline P, André M. “The effect of corneal diameter on soft lens fitting” (part 1). Contact Lens Spectrum 2002;17(4):56.

- Wolffsohn J.S. et al. “Bringing expertise back into soft contact lens fitting”. Soft Special Edition XXII.

- Rumpakis J. “New data on contact lens dropouts. An international perspective”. Rev Optom 2010;147(1):37-52.

- Syndicated incidence study by an independent research agency. Online survey with adults aged 15+ (n=16,279); France, Germany, Russia, and UK data combined (2013). Quoted by Aslam A. and Haskova J. “Understanding the Effects of Comfort on Contact Lens Dropouts”. Eye Health Advisor® by Johnson & Johnson, Edition One, 2014.

- Jones L. “Hydrogel contact lens materials: Dead and buried or about to rise again?” Contact Lens Update October 2013.

- Montani G., van der Worp E. “BCE vs DIA vs SAG”- Coverage from NCC 2016. Global Contact 2016.

- Caroline P. and Kojima R. “Sagittal Height Calculator based on Peripheral Corneal Angle Measurement”. Soft Special Edition WorldWide Vision XIV.

- Wolffsohn J.S. et al. “Impact of soft contact lens edge design and midperipheral lens shape on the epithelium and its indentation with lens mobility”. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:1690-96.

Academy

Academy